In the dark and dangerous world of the deep coal miner, the primary color is black and moments of beauty hardly ever happen at all. But once in a great while, miners probing into places in the earth’s depths, where no man has ever been before, come across something special.

Frank Cassman of Coaldale looked for such things. He was a man who appreciated the unusual during his 50-year career in and around the mines—uniquely colored rocks, sulphur diamonds (those silver-like bits and pieces embedded in rock found near coal seams) and pieces of petrified trees—wood turned to stone.

Frank Cassman of Coaldale looked for such things. He was a man who appreciated the unusual during his 50-year career in and around the mines—uniquely colored rocks, sulphur diamonds (those silver-like bits and pieces embedded in rock found near coal seams) and pieces of petrified trees—wood turned to stone.

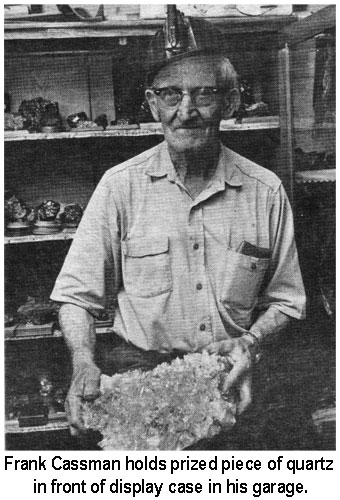

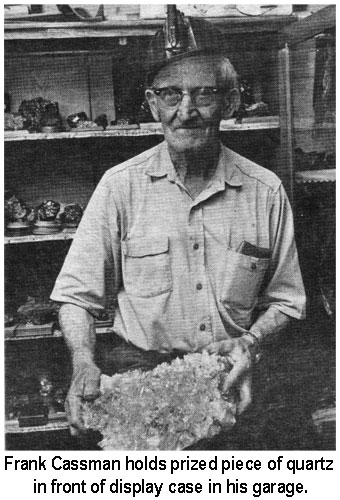

Cassman took a lot of it home. He mounted the pieces on pedestal-like bases of wood he cut and varnished. He wore out hacksaws cutting rocks into shape. He filled a display case in a small room off his kitchen with his mounted displays. When he ran out of room in his house, he got more display cases and put them in his garage. When these were filled, he built shelves. He filled them too. He put still more pieces on the shelves of an old refrigerator. Every wall in the garage is lined with mounted rocks, chunks of coal, pieces of quartz. Quartz looks like diamond.

There is a remarkable slab of it inside Cassman’s house at 112 Fisher Avenue. It occupies a special place on top of his display case. It is his most prized piece. About a foot in diameter, it is circular and looks like a tray of cracked ice or a heap of diamonds in the rough. The slab is surprisingly heavy. It glistens as though possessing lights of its own. The myriad faces of the clear crystal gleam, bouncing reflections in all directions.

There is a story behind it. The time was 1950. Cassman was the night shift boss on the seventh level of the Number 8 mine, a thousand feet under the mountain between Coaldale and Hauto.

His men were driving a chute through a cross vein. One of them came to him and said, “Frank, I struck a gold mine in the 702 gangway.”

He led Cassman to the spot. Quartz. In the light of his miner’s lamp, Cassman saw quartz. It glistened and sparkled along both sides of an open space about 16 inches wide following rock strata—walls of quartz, more quartz than Cassman ever saw—from the gangway floor to the ceiling “as far as I could see.”

Then and there he decided he’d get as much of it out as he could, a truckload at least.

“Tomorrow,” he told himself. He would get the quartz out tomorrow. “Tomorrow” became a couple of days, then a week, a little longer. Then tomorrow never came at all.

Within two weeks of the discovery of the cave-like quartz formation, fire broke out in the 702 gangway and emergency measures immediately went into effect. The area was quickly sealed off with a wall 30 feet thick. Behind it was Cassman’s truckload of quartz. It’s still there.

Frank Cassman said his mother was right: she told him not to put things off until tomorrow. Do it today. He has his souvenir piece of quartz and a good story that goes with it. Many men who have given years of their lives to one of the world’s toughest occupations have had to settle for less.

Frank Cassman of Coaldale looked for such things. He was a man who appreciated the unusual during his 50-year career in and around the mines—uniquely colored rocks, sulphur diamonds (those silver-like bits and pieces embedded in rock found near coal seams) and pieces of petrified trees—wood turned to stone.

Frank Cassman of Coaldale looked for such things. He was a man who appreciated the unusual during his 50-year career in and around the mines—uniquely colored rocks, sulphur diamonds (those silver-like bits and pieces embedded in rock found near coal seams) and pieces of petrified trees—wood turned to stone.